Industrializing European Modular Construction with Pop-Up Factories

Xavier Jaffray is the founder and president of LECO, a modular construction company in France. The Leco group specializes in the design and construction - in an industrial environment - of carbon-free buildings exclusively based on wood.

Before Xavier Jaffray launched LECO, a modular construction company, in France in 2013, he held management positions in both Toyota and Bic factories. He’d seen industrialized manufacturing up close. When he began researching the construction industry, he found that the companies that manufacture components for buildings — such as roof trusses, wall panels, and windows — are industrialized, but there was no industrialization in design and construction.

“Industrialization is based on the idea of manufacturing the same product over and over again, every day,” Jaffray says. Conventional construction doesn’t repeatedly produce the same product, so it doesn’t gain the efficiencies of industrialization. Part of the problem is that construction is necessarily localized and project-based. A social housing project here, a student dorm project there, a hotel project somewhere else.

Just because modular construction takes place in a factory, that by itself doesn’t mean it’s industrialized. “A real estate company might order 200 identical modules. But 200 units is not a mass-produced product,” Jaffray says.

A constant stream of identical products is typical of industrial manufacturing. When a factory isn’t producing anything, it continues to incur overheads, which is clearly inefficient. So, a challenge for modular construction companies is to eliminate factory overheads between projects. One way to do this is to have constant demand so there are no gaps between projects. This is ideal, but it’s not something a company can control. Another way is by eliminating the factory when there’s no demand. This is the route LECO has taken.

Going Local with Pop-Up Factories

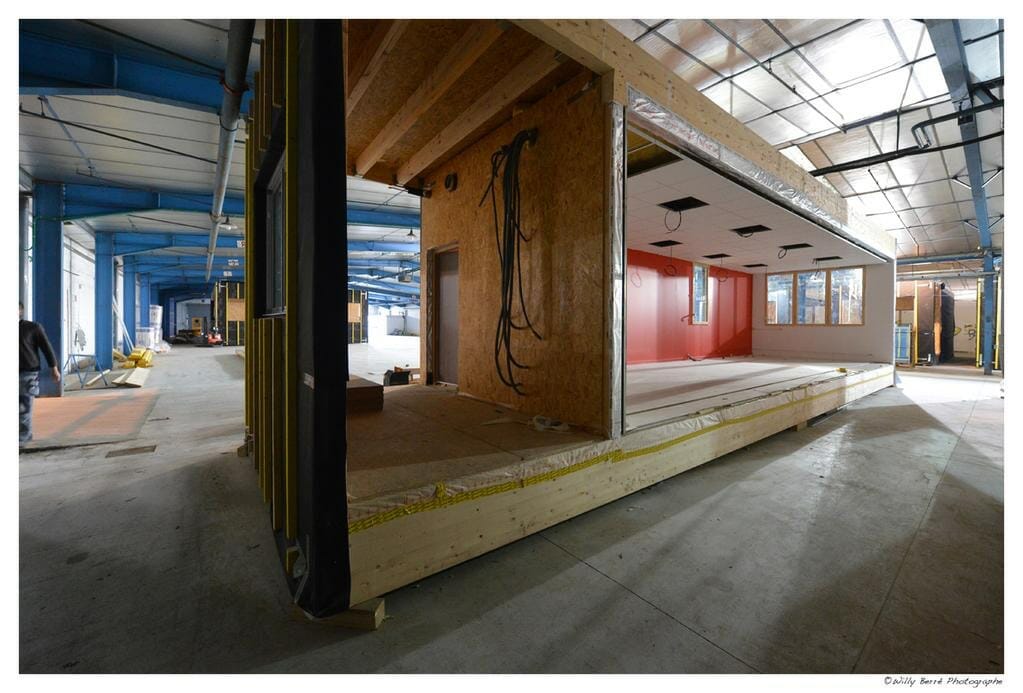

“The construction market requires agility,” says Jaffray. That is, construction companies need to adapt quickly to the location and volume of demand, without incurring overhead when there’s no demand for the product. Jaffray’s solution is novel. He uses what we might call ‘pop-up’ factories or what he sometimes calls ‘flying’ or ‘rocket’ factories near the project sites. LECO rents a large open space in a building, such as a warehouse or exhibition hall, to use as a factory. If there’s enough demand for LECO modules in the area, then the factory may continue to operate for two, five, ten years, or more. If there’s no demand, the factory closes — eliminating overheads. For as long as the factory is open, it’s constantly producing modules.

“It doesn’t make economic sense to have a big, permanent factory producing modules in one location and then transporting them long distances,” Jaffray says. LECO ships modules up to a distance of only 100 kilometers. LECO subcontracts with local companies on each project to transport the modules, lay the foundation, and set the modules in place. Most of the suppliers are also in the same area. They also transport the biggest modules they can each time — 5 meters wide and 20 meters long. “We’ve learned that it makes economic sense to deliver the maximum value on every truck trip.”

Eliminating overheads when a project isn’t going through means that LECO has been able to lower costs so that their timber modular construction is cheaper, as well as faster, than both conventional concrete or timber construction.

“Our first project using a temporary factory was a school for 600 students. It took three months in the warehouse-factory, and one month on the site to complete.”

Since then, LECO has opened seven temporary factories in France. Just as important as the temporary factories is the simple assembly process that can be taught quickly to unskilled local workers.

Labor and Logistics

For maximum efficiency, LECO needs to be able to get people working in the temporary factories quickly. They also need to draw from the pool of labor local to each factory. This means they can’t rely on being able to find skilled workers. Having to rely on unskilled labor requires an assembly process that is very simple and quick to learn. LECO’s factories do not cut the wood for their modules (eliminating the need for cutting machines and skilled workers to operate them). The pre-cut wood is delivered to LECO’s temporary factories for assembly.

Having a number of temporary factories, instead of one permanent one, creates logistical supply chain challenges. To address these challenges, LECO formed a dedicated supply chain division. LECO is a group of four companies, each of which has a different function: supply chain; employee training; engineering; and signing the contract with the client.

“Our supply chain company buys the wood and finds a company in the vicinity of the project who can cut it,” Jaffray explains. “We get the wood delivered to that company, and give them the files they need for their cutting machines. Then, the cut pieces are delivered to our temporary factory for assembly.”

Like McDonald's

Jaffray wants LECO to grow without becoming a huge company with high overhead. The way they’re doing this is by selling LECO licenses. “For those who buy a LECO license, we provide the engineering, we deliver the pre-cut components, and we train the employees. But they sign the contracts with their clients and employees, and they arrange for delivery and installation of the modules.”

LECO currently has two licensees in Germany and is working on getting licensees in the UK and the US. “I’m looking for people in the US who want to change the world,” Jaffray says with a laugh.

He compares his licensing business model to McDonald’s franchising. McDonald’s doesn’t have a huge factory where it manufactures Bic Macs to ship long distances to every McDonald’s restaurant. “McDonald’s franchisees hire unskilled workers locally at each restaurant. Those workers make the same products in all the different locations, using a simple process, with ingredients from the local supply chain. The restaurants in all their locations then serve the exact same products,” Jaffray says.

Recent and Upcoming Projects

Last year, in the heart of Paris, LECO built a three-story student dormitory on top of an existing three-story building. “With 400 people living within 100 meters of the construction site, there were concerns about construction noise over a long period,” Jaffray says. But LECO completed the project quickly and quietly.

For a month and a half, an exhibition hall in the north of Paris wasn’t holding any events. “So we rented the space for that period between two exhibition events,” Jaffray explains. “We spent four nights placing the modules and the maximum noise we made was briefly 80 decibels.” (According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 80 decibels is the same volume as city traffic from inside a car, and is significantly quieter than a motorcycle.)

For the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris, LECO will rent space from a large trade show company to build accommodation for 100 athletes. It’ll be needed for only two months. Like all LECO modules, they can be moved afterwards and be used for other purposes.

Jaffray explains that being able to relocate buildings is a more sustainable and economical solution than building new facilities when others are under-used. For example, an area may no longer need an elementary school building, but it now needs accommodation for college students. So instead of a building standing empty or under-used at the elementary school and building new college accommodation, the building can be relocated from the elementary school to the college.

“Relocatability is especially important for social housing,” Jaffray explains. “It’s easier and quicker to get approval if the housing is permitted for a limited period of time, eight years say, rather than permanently. That means that people can be housed sooner, but still in high quality buildings.”

About the Author: Zena Ryder is a freelance writer, specializing in writing about construction and for construction companies. You can find her at Zena, Freelance Writer or on LinkedIn.

More from Modular Advantage

Oregon’s Prevailing Wage Proposal: A Wake-Up Call for Modular Construction

In early February, 2024, the Massachusetts Board of Building Regulations and Standards (BBRS) released its proposed 10th Edition building codes. This draft included several amendments targeting modular construction that would have created an extremely difficult environment for the entire modular industry and could have eliminated the industry entirely in the state.

Behind the Design of Bethany Senior Terraces, NYC’s First Modular Passive House Senior Housing Project

As more developers seek to meet new regulations for energy efficiency, the team at Murray Engineering has set a new record. With the Bethany Senior Terraces project, Murray Engineering has helped to develop NYC’s first modular structure that fully encompasses passive house principles — introducing a new era of energy efficiency in the energy-conscious city that never sleeps.

How LAMOD is Using Modular to Address Inefficiency, Sustainability, and the Future of Construction

As developers, designers, and contractors seek to understand the evolving needs of the modular industry, no one is as well-versed in the benefits of going modular as Mārcis Kreičmanis. As the co-founder and CBDO of LAMOD in Riga, Latvia, Mārcis has made it his ultimate goal to address the inefficiencies of traditional construction.

From Furniture Builder to ‘Activist Architect’: Stuart Emmons’ Unique Journey

Stuart Emmons was fascinated by buildings at a young age. He remembers building sand cities with his brother during trips to the Jersey shore. His father gave him his first drawing table at the age of ten. Today, he is an experienced architect who received his FAIA in June 2025. The road he took is unique, to say the least.

Forge Craft Architecture + Design: Codes, Contracts, and Intellectual Property

Founding Principal and Director of Modular Practice for Forge Craft Architecture + Design, Rommel Sulit, discusses the implications of codes, contracts, and intellectual property on

modular construction.

Eisa Lee, the “Bilingual” Architect

Now as the founder of XL

Architecture and Modular Design in Ontario, Canada, she applies not just her education as a traditional architect but an entire holistic view on modular design. It’s this expansive view that guides her work on being a true partner that bridges the gap between architects and modular factories as they collaborate on the design process.

Tamarack Grove Engineering: Designing for the Modular Sector

The role of a structural engineer is crucial to the success of a modular project, from initial analysis to construction administration. Tamarack Grove offers structural engineering services — project analysis, plan creation, design creation, and construction administration — for commercial, manufacturing, facilities, public services, and modular. Modular is only one market sector the company serves but it is an increasingly popular one.

Engineer Masters the Art of Listening to His Customers

Since founding Modular Structural Consultants, LLC. in 2014, Yurianto has established a steady following of modular and container-based construction clients, primarily manufacturers. His services often include providing engineering calculations, reviewing drawings, and engineering certification

Inside College Road: Engineering the Modules of One of the World’s Tallest Modular Buildings

College Road is a groundbreaking modular residential development in East Croydon, South London by offsite developer and contractor, Tide, its modular company Vision Volumetric (VV), and engineered by MJH Structural Engineers.

Design for Flow: The Overlooked Power of DfMA in Modular Construction

Unlocking higher throughput, lower costs, and fewer redesigns by aligning Lean production flow with design for manufacturing and assembly.