Modular Multi-Family Case Study: The Graphic

About the Author: Kendra Halliwell, AIA, LEED-H AP is an Associate Principal, Practice + Design Team Leader, at ICON Architecture, Inc., a women-owned, Boston-based firm with award-winning work focused on innovative, sustainable mixed-use projects. Recently Project Manager for The Graphic, the largest modular construction project in the City of Boston, Kendra is leading several large scale multifamily modular projects through design phase.

The Graphic Lofts. Photo by Chris Rocco.

Architects and owners are increasingly drawn to modular construction. The premise of modular construction is that it promises to save time and money through repeatable elements that can be efficiently built in a factory, shipped, and connected in their final location. As construction costs increase and the housing crisis continues, modular construction provides a pathway to create high-quality housing.

ICON Architecture recently completed The Graphic, which is the largest modular (off-site) multifamily building in the City of Boston. Connected to an adaptive reuse building by an underground tunnel, 128 wood frame modular boxes make up 125 apartments in four stories over a steel and concrete parking podium.

Lessons learned from The Graphic

As an architecture firm starting our first modular project, we had questions about the process and the product. How would we provide our client with the level of design they expected?

Be aware that modular is not a typical design-bid-build process.

Each factory constructs their boxes differently, from typical length and width parameters to typical connections. The designer, builder, and manufacturer should collaborate to make the most of an efficient design process, but the project team may vary. For The Graphic, the manufacturer was subcontracted to the GC; in other scenarios, the manufacturer may directly contract with the owner.

Structural engineering for the modules and third-party inspection reviews may be provided or guided by the manufacturer, or they may be the responsibility of the design team. The lesson here is to “go modular” early and bring the owner, architect, general contractor, and manufacturing team together during the concept design phase so roles and requirements can be clearly outlined from the beginning.

Ask questions.

Constraints determined by the manufacturer include box size limits, transportation, construction methods, and structural and mechanical connections, all of which impact the design. Work with the manufacturer to understand the limits and tradeoffs of this construction type. A typical goal is to maximize the scope of work to be completed in the factory – this may include windows, exterior insulation, flooring, mechanical, electrical, fire protection and fire alarm systems, lighting, cabinetry, tile, and a primer coat of paint. Locating mechanical closets or shafts adjacent to the corridor wall will facilitate modular closeout, but that is a tradeoff for the design of the common spaces. These corridors are often left open to make connections and then closed-up by the general contractor on site. In multifamily housing, box width and length decisions impact the unit count and square footage. An early decision to standardize box width at 13’-8” across The Graphic building led to a clear structural meet-wall grid, but also resulted in relatively large apartment square footages.

For our more recent modular projects, we are incorporating a range of box widths, which cut across the entire width of the building, providing a larger width dimension for a living room, and a smaller width dimension for a bedroom.

Think outside the box, but respect the rules.

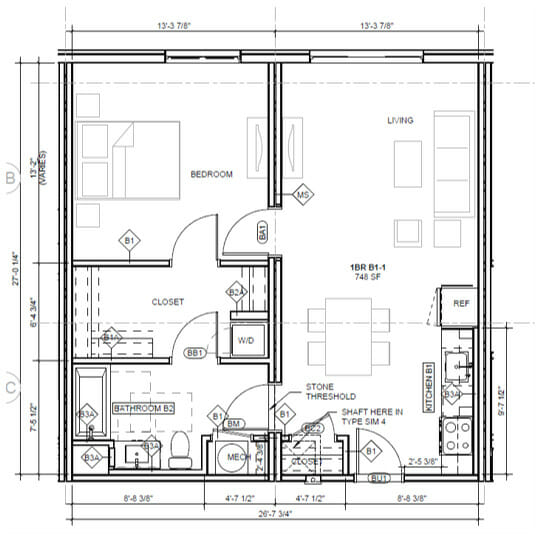

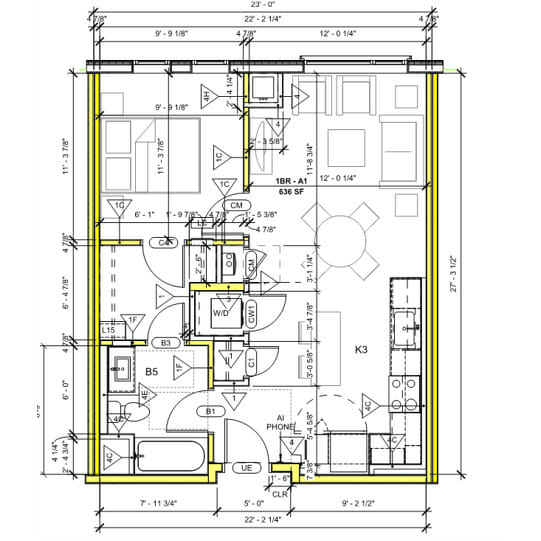

Unlike conventional construction, modular design must work within a tight and regular structural grid. While an opening may span ten feet (or more, with steel support) the design of programmatic uses and mechanical systems are best located completely on one side or the other, not straddling these “meet-walls”. The plans below depict two apartment layouts:

- This example conventional unit plan lays out the program spaces as needed, shifting as needed, creating a central zone for the supportive mechanical and storage spaces. The overall apartment width is narrow, and the wall between the bedroom and living room is a simple 4" wall. Building systems gather and run horizontally in the corridor ceiling on each floor.

- This modular unit plan locates mechanical closets, storage, and the apartment entry door completely on one side of the meet-wall or the other. In this building, box size was maximized for transportation. Mechanical spaces are close to the corridor and are grouped in a shaft to distribute in vertical stacks across the building.

Make the most of the individual boxes.

Utilizing individualized MEP systems where possible will reduce difficult connections between boxes. Because the double structural floor/ceiling system limits the available dimension between the boxes or through the framing to the corridor, it is imperative to minimize ductwork runs. To meet the state energy code requirements for fresh air ducting, we used the 4” interstitial space between boxes to tie bath and kitchen exhaust from the units through corridor ceilings into vertical shafts (2 per floor) to the rooftop ERV. As these connections were extremely tight in the corners of the corridors, we employed an all-electric system for in-unit HVAC.

Collaborate for condensed coordination.

The Graphic team met three times a week during the design development and construction documentation phases to ensure that mechanical systems fit into the modular boxes and that the connections from the boxes to building systems were well coordinated. Working through virtual design and coordination digitally cannot be emphasized enough: share the BIM file with the team regularly. Scope delineation between what is completed in the factory and what is completed at the site is a critical list of items on which everybody should agree. One of the benefits from this process includes simultaneous construction. As an example, the factory installed the modules’ finishes and cabinetry at the same time the onsite team constructed the podium.

Spend time at the factory.

The Architect/Engineers of Record and contractor/installers on site are ultimately responsible for closeout and affidavits. Our General Contractor maintained oversight of the boxes in the factory during construction, with observation from the representative of the state review board. The mechanical contractors also visited the factory so they were aware of exactly what was coming to the site. Additionally, visiting the factory allowed the team to see the benefits of modular construction firsthand: construction jobs are created in a safe, controlled work environment, with less waste and no exposure to weather.

Design with modular construction can be beautiful!

Modular is a tool. The process may be thought of as a spectrum that ranges from stick-built, to 2D panelization, to 3D volumetric modular forms. The design team may welcome what is initially viewed as design constraints and reframe how the typical building elements may be subdivided into smaller pieces that can be manufactured off-site and assembled on-site. For an architect, the constraints become design opportunities. The Graphic project, on a tight urban site in the Charlestown neighborhood of Boston, has no right angles. Our design embraced the geometry of these street edges, combining custom wedge-shaped boxes that crossed multiple apartments with separately constructed additive bay elements. These additive volumes create depth and interest on the regular planes of the façade.

ICON’s design team has incorporated these lessons, among others, into modular projects that are “on the boards”. Modular construction is not a silver bullet. It requires additional framing, so it does not save materials, and it requires more coordination at the beginning of the project. However, the modular process minimizes on-site labor by building off-site and lowers cost through the significant amount of time saved. As industry professionals gain familiarity with this tool, designing with open collaboration, this innovative construction method can lead to more efficient and creative applications of modular technology.

This article was first published in the Modular Advantage - May/June 2021 Edition.

More from Modular Advantage

Oregon’s Prevailing Wage Proposal: A Wake-Up Call for Modular Construction

In early February, 2024, the Massachusetts Board of Building Regulations and Standards (BBRS) released its proposed 10th Edition building codes. This draft included several amendments targeting modular construction that would have created an extremely difficult environment for the entire modular industry and could have eliminated the industry entirely in the state.

Behind the Design of Bethany Senior Terraces, NYC’s First Modular Passive House Senior Housing Project

As more developers seek to meet new regulations for energy efficiency, the team at Murray Engineering has set a new record. With the Bethany Senior Terraces project, Murray Engineering has helped to develop NYC’s first modular structure that fully encompasses passive house principles — introducing a new era of energy efficiency in the energy-conscious city that never sleeps.

How LAMOD is Using Modular to Address Inefficiency, Sustainability, and the Future of Construction

As developers, designers, and contractors seek to understand the evolving needs of the modular industry, no one is as well-versed in the benefits of going modular as Mārcis Kreičmanis. As the co-founder and CBDO of LAMOD in Riga, Latvia, Mārcis has made it his ultimate goal to address the inefficiencies of traditional construction.

From Furniture Builder to ‘Activist Architect’: Stuart Emmons’ Unique Journey

Stuart Emmons was fascinated by buildings at a young age. He remembers building sand cities with his brother during trips to the Jersey shore. His father gave him his first drawing table at the age of ten. Today, he is an experienced architect who received his FAIA in June 2025. The road he took is unique, to say the least.

Forge Craft Architecture + Design: Codes, Contracts, and Intellectual Property

Founding Principal and Director of Modular Practice for Forge Craft Architecture + Design, Rommel Sulit, discusses the implications of codes, contracts, and intellectual property on

modular construction.

Eisa Lee, the “Bilingual” Architect

Now as the founder of XL

Architecture and Modular Design in Ontario, Canada, she applies not just her education as a traditional architect but an entire holistic view on modular design. It’s this expansive view that guides her work on being a true partner that bridges the gap between architects and modular factories as they collaborate on the design process.

Tamarack Grove Engineering: Designing for the Modular Sector

The role of a structural engineer is crucial to the success of a modular project, from initial analysis to construction administration. Tamarack Grove offers structural engineering services — project analysis, plan creation, design creation, and construction administration — for commercial, manufacturing, facilities, public services, and modular. Modular is only one market sector the company serves but it is an increasingly popular one.

Engineer Masters the Art of Listening to His Customers

Since founding Modular Structural Consultants, LLC. in 2014, Yurianto has established a steady following of modular and container-based construction clients, primarily manufacturers. His services often include providing engineering calculations, reviewing drawings, and engineering certification

Inside College Road: Engineering the Modules of One of the World’s Tallest Modular Buildings

College Road is a groundbreaking modular residential development in East Croydon, South London by offsite developer and contractor, Tide, its modular company Vision Volumetric (VV), and engineered by MJH Structural Engineers.

Design for Flow: The Overlooked Power of DfMA in Modular Construction

Unlocking higher throughput, lower costs, and fewer redesigns by aligning Lean production flow with design for manufacturing and assembly.